By Kathryn White

Before the sun rose at 27th and Zuni the morning of Jan. 3, a multi-department city operation honed during Mayor Mike Johnston’s House1000 initiative had kicked into gear. Chainlink fence segments were erected around the perimeter of the over 150-tent community along 27th between Zuni and Alcott, continuing around the corner toward 26th and down Alcott Street toward West Byron Place.

Police officers stood ready, quietly talking to one another, releasing misty vapor breaths into the morning’s 23-degree air.

TV cameras lined up outside the fence, as did neighbors, housing advocates and volunteers from nearby mutual aid groups. A father and his teen daughter were inside the fence helping residents in one of the tents organize their belongings.

Others arrived: an operations team, a waste-removal truck, city outreach staff and staff from partner organizations. City workers zip-tied fence segments together and dropped off rolls of large yellow plastic bags near each section of tents.

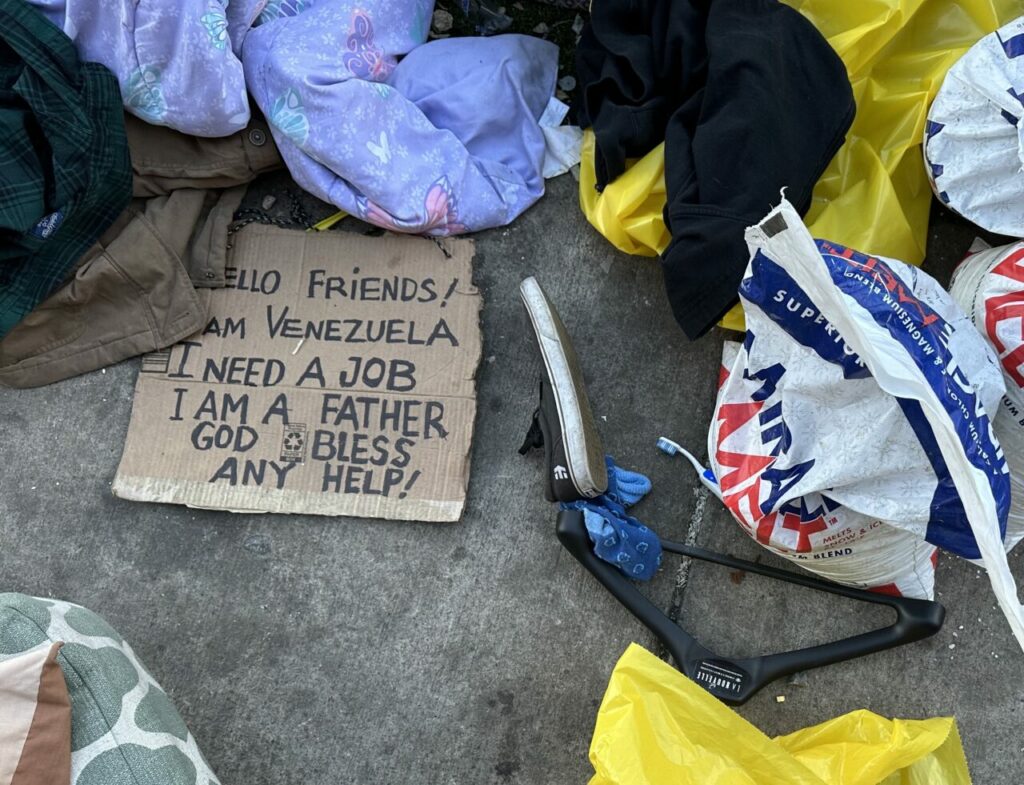

For those living at the camp, the morning of Jan. 3 wasn’t the rinse-and-repeat streamlined operation made efficient by the city in recent months. It was moving day. And because communication was a challenge, given language barriers and the size of the camp, some didn’t know what was happening and where they were to go.

On Dec. 27, 2023, the city taped flyers in Spanish and English on each tent, notifying occupants of the “multi-agency cleanup” that would take place Jan. 3. Anything they didn’t take with them would be removed to temporary storage where it would be disposed of after 60 days.

Migrants were given three options: they could apply for an apartment the city would help pay for, they could go to a congregate shelter, or they could receive a free bus ticket to anywhere in the United States. The latter option is made available to all migrants upon arrival in Denver. City spokesperson Jon Ewing put it this way, “If 200 people arrive by bus in a day, there’s a good chance that nearly half of them will either request a bus ticket that same day or within a few days.”

By Dec. 28, bilingual housing navigators — city staff, partner organizations and volunteers — set up shop at nearby Ashland Recreation Center and began matching encampment residents with apartments and helping them fill out applications. According to Ewing, around 100 people had been accepted into leased apartments by Jan. 3, though some would have to stay in the city’s congregate shelter until leased units were ready for them. Over 300 rental applications had been submitted by Jan. 3.

At 8:30 a.m. the day the camp was to be dismantled, outreach workers wearing yellow vests began going tent-to-tent, explaining that each person could bring two suitcases and two yellow bags full of belongings with them to the shelter. Buses would begin departing for shelters at 10 a.m.

V Reeves, an organizer with the housing advocacy group Housekeys Action Network Denver, also spent the day at the site, helping camp residents understand their options and the process. Reeves and others wondered if the pre-dawn arrival of fencing and police had been perceived as threatening.

“My hope is that we don’t lose people to fear,” Reeves said early that morning. “That we don’t have people who leave and have nowhere to go and then are further displaced and separated from the rest of the community, where we can’t connect with them and support them.”

Council President Pro Tem Amanda Sandoval (Northwest Denver District 1) and Council members Diana Romero Campbell (southeast Denver District 4) and Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez (at-large) joined outreach workers.

Sandoval said she visited the camp every day for the last few months, looking for families living in tents outdoors who the city will house in its hotel-style shelters. She monitored city services like trash removal and portable toilets and checked to make sure pathways for fire department access were clear.

“My hope today is that we get everyone indoors and off the street, no longer living in tents,” Sandoval said. “And that we get them into wraparound services, focused on housing navigation. And continue to get any families who are living outdoors back indoors.”

Mayor Mike Johnston arrived at 10 a.m. He walked along W. 27th from Alcott down to Zuni, speaking with people and listening to their concerns about what quickly became apparent as a top priority: work.

Johnston spoke to the press about the challenges the city faces with 150-250 new arrivals each day. Johnston is asking for Colorado’s governor and congressional delegation to partner with him in a focus on new federal work authorization measures for recent arrivals, state and federal financial support and a coordinated entry system like what has been used for other refugee groups.

Johnston said of North Denver, “Neighbors [here] have come forth at every single stage with food, with clothing, with support, with help to housing. People have set up nonprofits on their own to provide housing and support. We are deeply grateful for their generosity and for their spirit and their support.”

“We welcome [community members] to continue that support in our new locations,” Johnston went on. “The most urgency is for housing navigation. We need Spanish speakers who can help people fill out housing applications. We also need pro bono lawyers who can help people on either work authorization applications or on court dates. And so our most important need is for us to continue to channel the generosity of those people who are engaged.”

By 5 p.m. on Jan. 3, the last bus had departed and a handful of people milled about, going in and out of the former Quality Inn being used for family housing.

On Jan. 4, diggers and trash trucks took away anything that remained on the streets and sidewalks, including many tents.

On Jan. 5, city workers power-washed the areas where the encampment had been.

And while 277 people, according to Ewing, moved indoors from the camp Jan. 4, the next day 226 more people arrived by bus to Denver from Texas.

“Every day, dozens if not hundreds of people are going to end up on the streets again,” said Reeves, “because they continue to have a time allotment in the hotel. People are continuing to arrive to Denver, migrants arriving for the first time to Denver, so you might be able to support the people right now camped outside, but next week there’s going to be another some 100 or multiple hundreds of people. I don’t see this as being a sustainable plan.”

Visit www.denvergov.org/migrantsupport to learn about ways to support new arrivals to Denver.

Be the first to comment