Ryan Leach’s recent job experience includes teaching computer programming internationally, but these days he sounds more like a community or union organizer. Leach, a tenant in the Capitol Hill neighborhood, has been organizing his fellow tenants at the Acacia building to collectively negotiate with the building’s management.

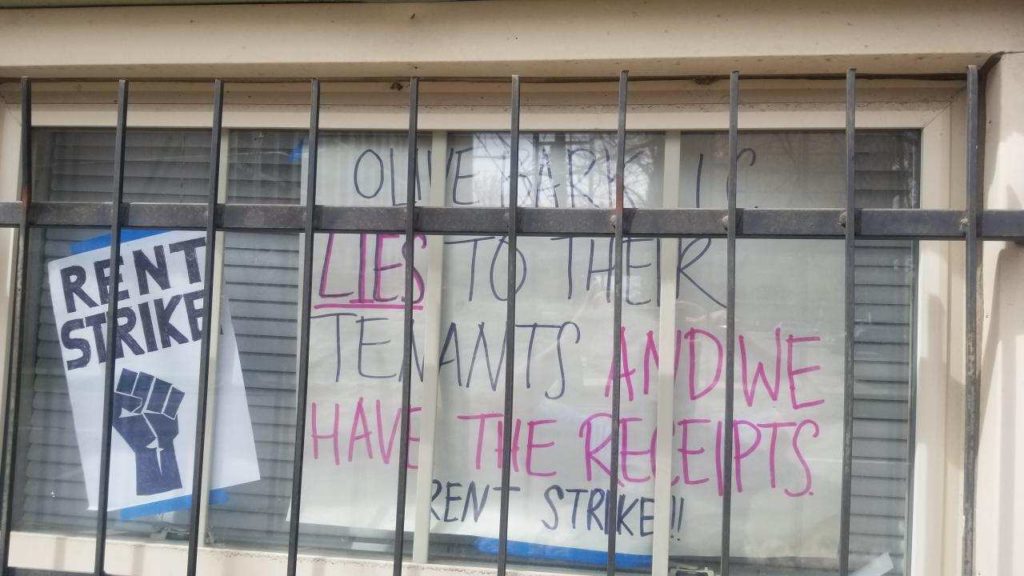

Photos courtesy of Ryan Leach

Leach said the Acacia Tenants Union (TATU), have been pushing their building management company Olive Bark to work with them collectively instead of as individual tenants. The disagreements are what you see in many articles about renters and landlords during the COVID-19 crisis: rent demand letters, evictions being halted by state and federal authorities, and all parties saying they can’t afford to pay their bills. Leach shared an email from management referenced late fees despite a moratorium on them. Building management said it was a misunderstanding and all late fees have since been waived. Leach said building management was posting letters that read like eviction demands despite a moratorium on those as well. The spokesperson for the company said they weren’t intended to read like eviction notices; they were only 10 day demand letters and the company was following the law. This is the back and forth of many tenants and landlords as unemployment numbers surge.

The Acacia story stands out in Denver because tenants unions aren’t a concept many Denverites are familiar with and if Leach is successful in his negotiations, other tenants across the city may follow suit.

“Opening negotiations were a shot in the dark to be honest,” said Leach who has organized what he says is a third to half of the tenants in his building to negotiate with the building’s property managers. To put that percentage in perspective, labor unions in Colorado need 30% of employees to sign up to hold an election to unionize a workplace. This means if similar laws recognized tenant unions, Leach would have more than enough support to hold an election to form a union. While tenant unions are not usually recognized in law the same way as workplace unions, the parallels are striking.

Leach said while specific demands like a percentage reduction in rent are open to discussion, the main reason they are organized is because individual residents weren’t getting responses, something the company disputes. “We would be happy if they came to the table and negotiated with us in good faith,” said Leach.

The building management also deployed a response labor unions are accustomed to seeing from company management: bringing in outside help. In this case, a media request to Olive Bark wasn’t answered by the company employee who had handled previous requests from other media outlets, but was instead answered by Krista Crouch with the Public Relations Firm Novitas Communications. Crouch is now serving as a spokesperson for Olive Bark and Acacia. Novitas advertises themselves as “Denver’s Top Crisis Firm.”

Crouch said they are trying to work with residents, individually or collectively, and that Olive Bark is making generous offers to residents out of work. “This is coming from a good-hearted place,” Crouch said of their offers to create payment plans for residents. The average rent in the building is $1,100/month according to Crouch, and payment plans required tenants to pay 50% of their rent on time. The other 50% would be paid off in subsequent months by adding $100/month until the balance is paid, something Leach said was not feasible for tenants already struggling to pay the $1,100. No tenants had been offered a reduction in rent, according to both parties.

Leach is encouraging a rent strike, where a large group of residents all refuse to pay in solidarity with others even if they can afford to pay that month. If work stoppages are one of workplace organizer’s most aggressive tactics, rent strikes are likely their tenant union analogues. One of TATU’s demands said that the company should be using all federal provisions available to them, including one that allows mortgage payments to be suspended and paid at a later time, which he believes would relieve pressure on all parties. He’s also encouraged all residents to only communicate to management in writing, which he believes ensures they are being treated equally and fairly, and to create records of conversations.

Crouch said that rent strikes of that sort can actually hurt those who they are intended to help: “If somebody can afford to pay their rent, they should pay their rent. If they don’t, they are taking resources away from people who need them,” adding that management companies can’t provide help to a few residents out of work if no one is paying. She also said the company that owns the building has availed themselves of federal loans to bring back furloughed staff, but don’t want to use the forbearance the CARES act allows because it could damage the company in the long run.

Wendy Howell is the Deputy Director of Colorado Working Families, a progressive labor-aligned organization. She used to be a tenant organizer in New York City and believes renters organizing together can have more effect than separate. “What we see both in the workplace and in housing is that the people with money are organized…we don’t see it as much with the people who are impacted by their decisions,” said Howell. She believes rent strikes and collective bargaining are tools renters may start using more. “They’re finding the power to push back economically.”

Michelle Lyng, a spokesperson for Colorado Apartment Association, says their members are going above and beyond to help renters in crisis, and the association is giving $25,000 to a fund intended to help Colorado renters in crisis. She said members have pledged around $50,000 to match them, but said that being a landlord doesn’t mean someone is wealthy. “Honestly not every member can do payment plans,” noting that small landlords are in a tough spot and larger buildings are having to furlough employees when tenants don’t pay.

One point that Lyng and Leach seem to agree on is that the government response hasn’t made meaningful improvements to the situation. “It demonstrates a lack of understanding of the rental market,” Lyng said of a resolution passed by the Denver City Council that encouraged state and federal elected officials to freeze rent and mortgages. The apartment association also released a statement criticizing Governor Polis’ moratorium on evictions. “We also have concerns that the Governor is tying his authority to enact an eviction moratorium to an amorphous concept of economic stability, which has no statutory definition and is a largely subjective measure,” read the May 1 statement. Regarding Denver’s actions, Leach said he was “happy to see a unanimous vote, but it has to go further,” but highlighted two freshman council members he saw as allies: Candi CdeBaca and Chris Hinds.

Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca, who represents parts of North and Central Denver, also said the city needs to do more, concerned that “100,000 or more in Denver could be facing eviction,” due to lack of payment if the crisis continues. She doesn’t believe the city’s rental assistance program (TRUA) had enough capacity before the current crisis and she’s concerned the most vulnerable won’t be able to receive funds as demand increases. A spokesperson for the city said the fund is still operating despite the increased strain: “Call volume to the 311 center, seeking info on TRUA, has increased more than 5X since prior to the onset of COVID-19. Likewise, the number of TRUA applications sent to residents per month has increased by 775% as compared to prior to COVID-19 locally.”

Be the first to comment